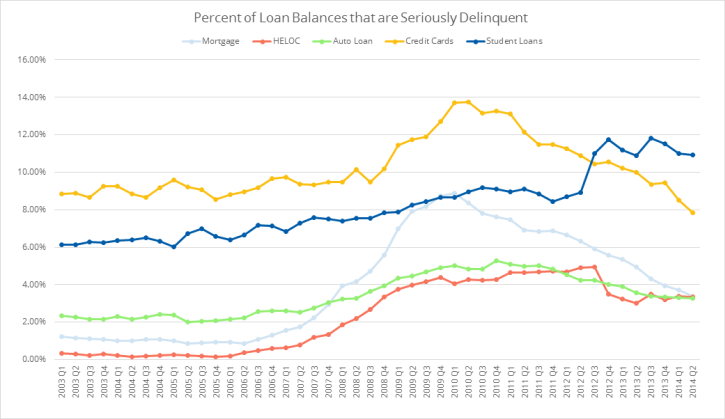

Data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York concerning serious delinquencies of various types of consumer debt shows a strange spike in serious student loan delinquencies in Q3 of 2012. The data was published in the Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit (August 2014) and is reproduced in the following graph. A loan is considered to be seriously delinquent when it is 90 or more days delinquent.

There was no catastrophic economic event in Q3 of 2012 that could be responsible for a sharp increase in serious delinquencies from 8.92% of student loan dollars to 11.73% of student loan dollars. This data suggests that the number of student loan borrowers with a serious delinquency increased by about a third in just two quarters.

The onset of the spike of mortgage delinquencies started in Q4 of 2006, leading to the subprime mortgage credit crisis. Credit card delinquencies started spiking in Q2 of 2008, when credit card issuers began adopting stricter underwriting criteria and Home Equity Lines of Credit (HELOCs) became less available for refinancing credit card debt. Mortgage delinquencies and credit card delinquencies peaked in Q1 of 2010.

The most likely explanation for this spike in education loan delinquencies is a delay in serious delinquencies due to the impact of the Ensuring Continued Access to Student Loans Act of 2008 (ECASLA, P.L. 110-227). Prior to enactment of this legislation, borrowers of Federal Parent PLUS loans entered repayment within 60 days of full disbursement. The ECASLA legislation, which was effective on July 1, 2008, allowed parent borrowers to defer repaying the Federal Parent PLUS loans while the undergraduate students on whose behalf they borrowed were still in school and for six months after graduation.

Parents of new students were more likely to take advantage of the new deferment option than parents of returning students. Borrowers have a tendency to use the same options as during previous years, even if new options become available. Also, data from the 2011-12 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) demonstrates that parents are more likely to borrow Parent PLUS Loans during the junior and senior years than during the freshman and sophomore years.

Parents of new students first enrolling in 2008-2009 would not enter repayment until fall 2012, coinciding with the increase in serious delinquencies.

If this interpretation is correct, that the spike in education loan delinquencies that began in Q3 2012 is due largely to the deferment of parent education loans, then the concern about an increase in student loan delinquencies may be misplaced. Disaggregating the delinquency data according to the type of loan might confirm that the spike in serious student loan delinquencies is mostly due to Parent PLUS Loans. The U.S. Department of Education released 3-year cohort default rate data for Parent PLUS Loans prior to Session 3 of the 2013-2014 negotiated rulemaking concerning the definition of an adverse credit history, showing a sharp increase in the default rates, from 1.8% for the FY2006 cohort to 5.1% for the FY2010 cohort.

If the spike in education loan delinquencies follows the pattern of the spikes in mortgage and credit card delinquencies, the percentage of student loan borrowers with a serious delinquency should start decreasing over the next several quarters.

It is also possible that the shift in federal education loan volume from the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program to the Direct Loan program in 2010 may have had an impact, since Parent PLUS Loan denial rates in the Direct Loan program were half the denial rates in the FFEL program, based on an analysis of data from the 2007-08 NPSAS which demonstrates a 43% denial rate in FFEL program and a 22% denial rate in the Direct Loan program. However, the higher denial rates in the FFEL program may have been due to errors in the credit underwriting that are not necessarily predictive of loan delinquency and default.