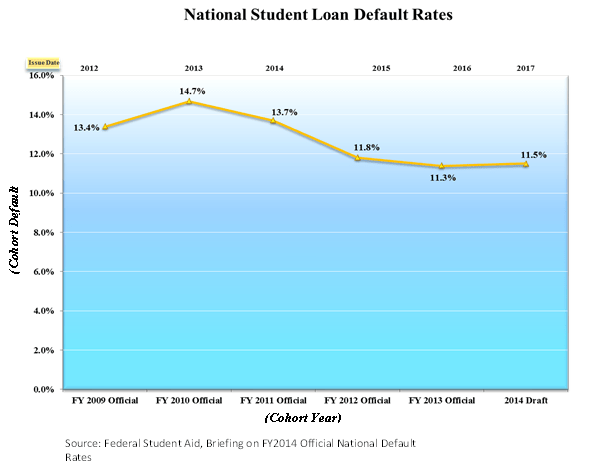

One of the leading indicators that student loan borrows may be in a tug-of-war with repayment is the national student loan default rate. On September 27, 2017 the U.S. Department of Education released the official FY 2014 3-year federal cohort default rate (CDR). The rate increased to 11.5%, up from 11.3% in FY 2013. The CDR is calculated by taking the number of students (cohort) who entered repayment during the 2014 fiscal year—in this case Oct. 1, 2013 to Sept. 30, 2014—and divides this figure by the number of borrowers who defaulted on their loans within the 3 year tracking window (Oct. 1, 2013 to Sept. 30, 2016).

The U.S. Department of Education releases preliminary cohort default rate data to schools in February or March and publishes official cohort default rates in mid to late September after schools have had the opportunity to challenge errors in the draft data.

Cohort default rates at private, non-profit colleges increased by 0.5%, albeit still lower than other sectors. Community colleges and for-profit colleges continue to produce double-digit CDRs, as evidenced in the table below. Overall, the 3-year CDR increased by 0.2% across the board—a slight increase but enough to warrant ongoing concern that many borrowers may be over their heads in education related debt. In the case of the FY 2014 cohort, this amounts to nearly 561,000 borrowers. Additionally, this recent rise in the national CDR marks the first increase in the last four years.

| Institution Type | FY2012 CDR | FY2013 CDR | FY2014 CDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public, 4 year | 7.6% | 7.3% | 7.5% |

| Public, 2 year | 19.1% | 18.5% | 18.3% |

| Private Non-Profit, 4 year | 6.3% | 6.5% | 7.0% |

| Private For-Profit, 4 year | 14.7% | 14.0% | 14.6% |

| Overall | 11.8% | 11.3% | 11.5% |

If you’re a student, this information may beg the question of, “why should I care?” Well, for starters, the cohort default rate will vary by school. If any college or university has a CDR greater than 30% a year for three years in a row, the institution may lose eligibility for federal student aid. In essence, they would face sanctions from the U.S. Department of Education. This puts programs at risk for future generations of students. Moreover, in a single year if a given college/university has a published CDR that is more than 40%, it would likewise face sanctions.

For taxpayers, the implications are quite clear. After all, we are talking about a federal program which is subsidized through tax dollars. According to Heritage.org, in 2016 over 40% of students with federal student loans (roughly 9 million borrowers) were either in default or delinquency, or had postponed payments. In a relevant Washington Post article, it was reported that the Government Accountability Office estimated taxpayers would ante up close to $108 billion to help borrowers. Simply put, taxpayers shoulder the burden when student loan borrowers cannot pay; making the national CDR a measurement of interest to the nation, not just those in higher education or politics.